The study design must ensure validity and reliability, whereas relevance must be addressed by identifying precise objectives, choosing appropriate scientific methods, recruiting representative target populations and by adhering to established ethical standards. Identifying the objective is really all about asking the right and the most significant questions. If we succeed in our endeavour, only this will move the field forward.

Before you start

There are six key steps to have in mind when designing a research study:

Identify clearly and precisely the question to be addressed.

Understand the current status of the field, and get an overview of the relevant literature.

Formulate the hypothesis.

Identify the data needed to test the hypothesis and describe how the data will be collected.

Establish a data analysis plan to streamline the project and identify any weaknesses in the design.

Ensure that the project follows established ethical standards and relevant regulations.

How to choose the right study design

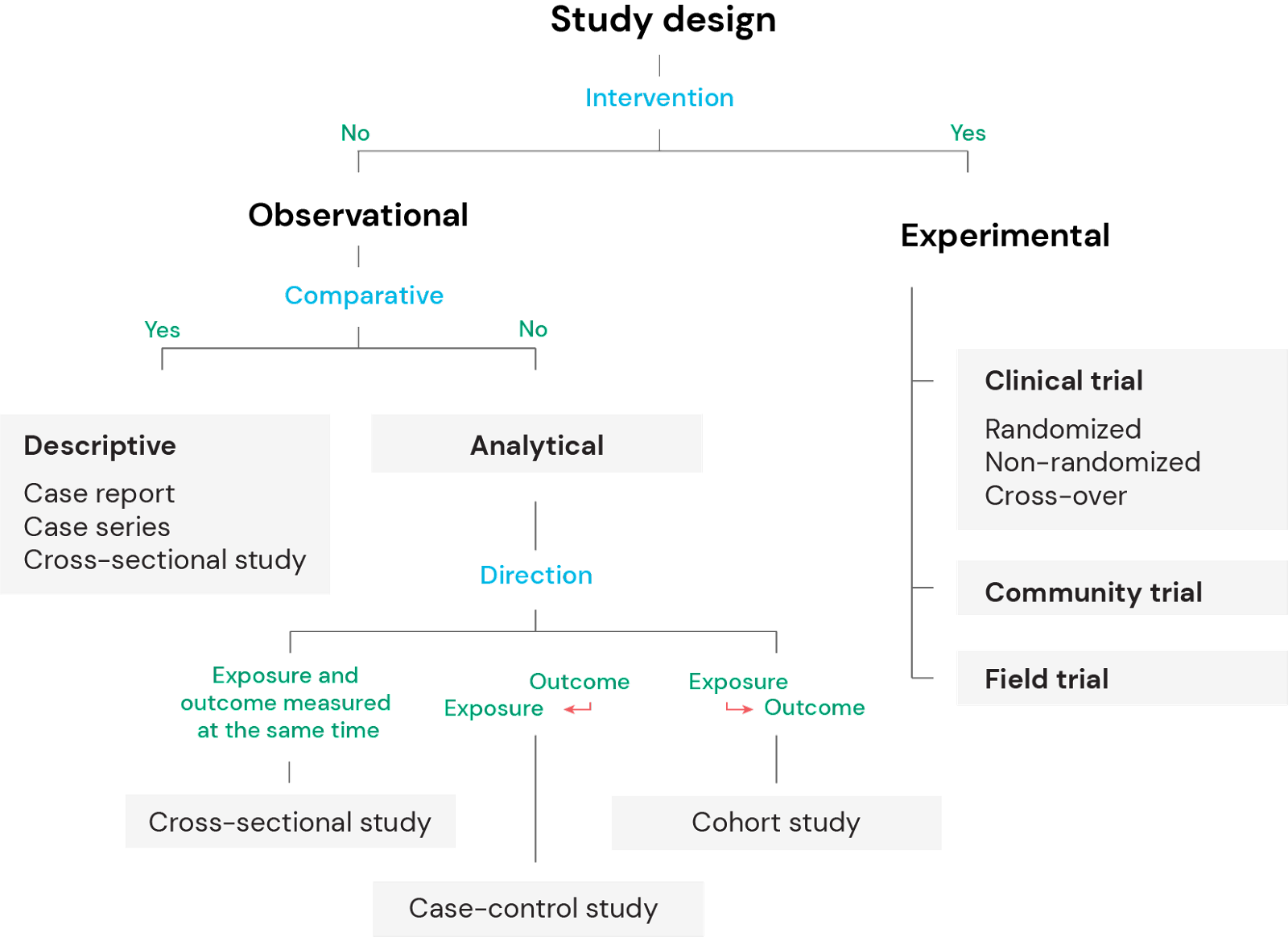

Choosing the right design determines how the study will be conducted, and how the data will be analysed using appropriate statistical methods. Correct study design ensures the validity of the conclusions. There are several factors that will guide the design, but a fundamental question is whether the aim is to purely describe a phenomenon, identify associations or correlations, or to test a hypothesis to establish causal relationships.

Observational versus experimental studies

There are two major groups of clinical study designs; observational and experimental.

Observational studies can be further divided into descriptive and analytical. Descriptive studies do not intend to identify potential associations or correlations, whereas analytical studies are hypothesis-generating and aim to identify associations or correlations between the variables.

Experimental studies, on the other hand, involve an intervention to modify or control variables in order to test one or more hypotheses and identify potential causal relationships.

Factors that influence the choice of study design

Several factors influence the choice of study design, including funding, time constraints, the nature of the disease, condition or phenomenon being studied, availability of data or study subjects, and the current status of the field. It is also crucial to determine whether the study aims to identify associations, correlations or causal relationships. In epidemiological studies, several criteria are used to evaluate potential causation, where temporality is one of the most important together with strength of the association, consistency (the association has been identified in multiple studies under different circumstances) and gradient (i.e. dose-response). Temporality (the effect follows the exposure) is best studied in prospective studies such as prospective cohort studies and in experimental studies (i.e. clinical trials). Importantly, causal relationships cannot be proven in descriptive studies.

1. Observational studies

Observational studies, also called epidemiological studies, can be divided into descriptive and analytical studies. In descriptive studies the investigator purely describes the natural relationship between factors such as the exposure and/or the outcome, whereas in analytical studies the aim is to identify an association or measure a correlation between the exposure and the outcome.

2. Case reports and case series

Case reports and case series are retrospective studies that provide detailed descriptions of a particular case or a series of cases with similar presentations. They usually contain a review of the field, and a comprehensive description of the particular cases and what makes them unique. However, case reports and case series do not make any statistical inferences or generalizations, and they do not contain data from comparative groups of patients or individuals. Thus, case reports and case series can draw attention to a new phenomenon, clinical presentation or potential new disease and spark further investigations. However, the study design can not be used to identify associations, correlations or causal relationships.

3. Cross-sectional studies

Cross-sectional studies are also retrospective, but can be both descriptive and analytical. An analytical cross-sectional study evaluates a potential association between an exposure and an outcome. Because the prevalence of both the exposure and the outcome is measured at the same time, a cross-sectional study can not assess temporality, which is an important guiding principle for making assertions of causality.

4. Case-control studies

Case control studies are used to retrospectively compare two or more groups of subjects, and to identify factors that are associated with an outcome. For example, the study design is used to look for potential risk factors for development for a disease by comparing a group with the disease and one without. The study design can be used to test hypotheses by identifying associations and correlations, but it can not be used to prove causal relationships. Case-control studies are often used to study rare conditions as a prospective cohort study would require a very large sample size in order to accumulate the sufficient number of cases, a long study period, or both. As such, case-control studies are both cheaper and less time-consuming than prospective cohort studies.

5. Cohort studies

In cohort studies, two or more groups with different exposure or risk factors are selected and then compared for differences in the outcome such as a disease. Thus, this is the opposite of the design of case-control studies, where the groups are selected based on the outcome itself.

Cohort studies can be prospective and retrospective. All retrospective study designs are more prone to selection and recall biases, however they are obviously much less time consuming to conduct and cheaper. To prevent selection bias, the comparison groups are supposed to be as similar as possible except for the exposures or potential risk factors that are studied. This can to a certain extent be controlled for by the investigators. Recall bias on the other hand, i.e. individuals with the disease are more likely to remember exposures or risk factors than healthy controls, is more difficult to compensate for.

6. Experimental studies

Experimental studies, also known as interventional study designs, represent the pinnacle of clinical studies with respect to scientific evidentiary quality and with most power to suggest or prove causal relationships. These study designs are testing hypotheses and the investigators control the exposure and assess the outcome.

Experimental studies can be conducted both with and without comparison groups. Comparative studies are clearly more convincing in demonstrating causal relationships, as the intervention being studied is distributed to one group and the other represents a control to confirm that the outcome is related to the invention, and not due to time, chance or an unrelated factor.

7. Randomized clinical trials

Among the various experimental study designs, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the most reliable and provide the most valuable data. The importance of randomisation is that the treatment groups will be balanced in known and unknown prognostic factors. It is important that the intervention group and control group are run in parallel so that the observation phase occurs in the same period in time for both groups. Combining blinding with placebo further effectively reduces the risk for biases. Double blinding means that neither the investigator nor the subject are aware of what treatment the subject is undergoing. It may be impossible to blind the subjects, for example when the treatment is a surgical intervention or an educational or informative procedure, but it is often possible to ensure that the investigators that evaluate the outcome are unaware of the treatment.

Even though the scientific quality may be very high, and the validity of statistical analyses is solid, the real-world relevance may be of limited value. To ensure relevance, the endpoints should be well-defined, reproducible and clinically meaningful. However, highly selected subject groups in a clinical trial of a new drug may reduce the relevance if the drug is intended for use in a vastly biologically heterogeneous patient population. Homogeneous study groups may also facilitate identification of statistical significant relationships that may not translate into meaningful treatment benefits in clinical practice.

To ensure real-life relevance of clinical trials, the study population should be representative of the targeted patient population in general with respect to biological heterogeneity, age, gender, race, and variation in disease severity and manifestations of symptoms. If conducted in a scientifically sound manner, the prospective design combined with controlled intervention, balanced groups for comparisons and bias elimination with randomization, placebo and double blinding provide, RCTs provide strong scientific evidence for identifying causal relationship between the intervention and the outcome.

8. Community trials

In contrast to clinical trials where treatments are assigned on an individual basis, field and community trials are study designs where the intervention is delivered to groups of subjects. In community trials, the intervention is allocated to entire communities or neighborhoods regardless of whether the individuals have the condition/disease or not. This type of trials are typically conducted in studies of preventive health measures such as the historical studies of fluoride treatment to prevent dental carieswhere one community received treatment and the other did not in order to determine effectiveness.

9. Field trials

Field trials are preventive or prophylactic trials where subjects without the disease are allocated with or without randomization to different preventive intervention groups. Most trials of preventive measures, such as immunizations or health education, are field trials where the subjects are representative for the general healthy population. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are usually less stringent in field trials compared to clinical trials, and the results from field trials are therefore easier to generalize into real life treatment benefits.

Overview study designs

Figure 1: Overview of study designs

More From Ledidi Academy

The difference between association, correlation and causation

- Statistical analysis

- Tips and insights